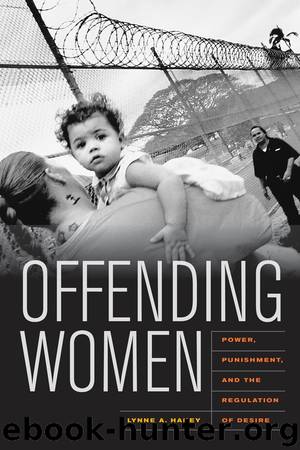

Offending Women by Haney Lynne A

Author:Haney, Lynne A.

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of California Press

Published: 2012-01-22T16:00:00+00:00

FIVE The Empowerment Myth

SOCIAL VULNERABILITY

AS PERSONAL PATHOLOGY

On a summer afternoon, a group of inmates gathered in Visions’s art room for the first meeting of one of my creative-writing classes. It was the third such course I had offered at Visions, so I began with a writing exercise that worked with the other groups: I asked the women to list ten emotions or sentiments, which I then wrote on the blackboard. “Sorrow,” Rosa yelled. “Grief, fear, and depression,” Chanel added. “No, you’ve got to put anxiety and frustration at the top,” Melissa demanded. “No way,” Claire interjected. “Guilt and regret should be up there.” The list concluded with “disappointment” and “loneliness.” Their list was strikingly similar to those produced in the previous classes so I raised an issue I resisted mentioning to the others. “These are all negative emotions,” I noted. “What about positive . . . ” Before I could finish my sentence, Rosa jumped in. “Girl, I thought you knew this place. Didn’t you learn anything? This place is all about depression and guilt. What positive feelings do you want from us?”

These were hardly the sentiments one would expect from the “empowered” selves Visions claimed to be producing. The promises the staff made to their charges were exceptionally lofty: if they worked the program, the women would lead lives free of addiction. Once freed from addiction, their self-esteem would soar. And once full of self-esteem, personal empowerment and transformation would soon follow. Nowhere in this formula were the fears and anxieties expressed by the women in my writing class.

The Visions staff members were not the only ones with high hopes for their program. Social scientists, activists, and journalists often look to facilities like Visions as promising alternatives to punitive corrections.1 Their optimism comes from two main sources. First, some see hope in the structure of these programs. Located outside the confines of traditional prisons, alternative-to-incarceration programs have become a model for progressive penal reform and a way to get inmates out of the much-maligned formal penal system. The assumption is that serving time in the “community” is necessarily better than living behind bars because community-based facilities are thought to be less punitive. This assumption also underlies many analyses of women in prison, which often presume that penal institutions become more “women friendly” as they move outside the official boundaries of the state.2 As a result, these analyses almost invariably conclude with calls to place female offenders in community settings where their needs will be understood and addressed.3 Even those scholars who are otherwise suspicious of recent shifts in governance remain optimistic about such programs, with one suggesting that they can breed a “radical politics of rights and empowerment.”4

Second, there are those who have high hopes for the therapeutic aspects of penal programs like Visions. For decades the U.S. penal system has been accused of warehousing inmates and giving lip service to the idea of rehabilitation.5 Such accusations tend to be coupled with calls for penal programs that address the

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 1 by Fanny Burney(32558)

The Great Music City by Andrea Baker(32018)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 2 by Fanny Burney(31956)

Cecilia; Or, Memoirs of an Heiress — Volume 3 by Fanny Burney(31941)

We're Going to Need More Wine by Gabrielle Union(19046)

All the Missing Girls by Megan Miranda(16023)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14506)

For the Love of Europe by Rick Steves(14121)

Bombshells: Glamour Girls of a Lifetime by Sullivan Steve(14073)

Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell(13370)

Norse Mythology by Gaiman Neil(13363)

Fifty Shades Freed by E L James(13239)

Mindhunter: Inside the FBI's Elite Serial Crime Unit by John E. Douglas & Mark Olshaker(9339)

Crazy Rich Asians by Kevin Kwan(9290)

The Lost Art of Listening by Michael P. Nichols(7506)

Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress by Steven Pinker(7311)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6765)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6621)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6279)